Spoilers below.

Tyler: When you and I broke down our top ten of the 21st century, Norman, I made reference to tonight’s film, 25th Hour, slotting it a kind of honorable mention, noting it was “just imperfect enough” to miss the list proper.

It was after making that observation that you suggested we give the movie a revisit, and now, man, I just don’t know about my top ten anymore. This is one of Spike Lee’s career-peak joints.

Norman: Cue dramatic music, cue shots of ground zero, it’s a Tyler and Norman Joint!

I had not seen 25th Hour in probably 23 years. And when I did see it, it was on a VHS tape, so not optimal. Seeing it again was a treat, but I also came away a little mixed in my reaction.

Tyler: It’s a polarizing kinda picture. I once, in my early twenties, suggested it for a family movie night with my then-girlfriend and her jovial parents. I recall still her father, a fine man, half-muttering “Well that was weird.”

Norman: A perfect reaction, actually!

I felt a little the same the minute after the credits started to roll. I’ve had a few days to think about it, and I think I have some idea of what Lee was doing, but it’s not a movie that immediately reveals itself in the moment.

Tyler: I’ve watched it quite a few times, to the point where I saw certain moves and heard particular lines coming. This time around, though, it felt much better than “just imperfect enough.” It’s a passionate portrait of New York, thing one, and in a non-coastal way that brings the vibrance of that city to the forefront—not unlike the incandescent world of Do The Right Thing. DOTR‘s world is a bit of a fantasia, lovely and bright but gutting and rotten with racism; 25th Hour, meanwhile, is at times an overt valentine to the multicultural metropolis at its best.

That said, this is not just a film about New York City. The country around it is pretty beautifully on display.

Norman: The main thing that I kept thinking about was how Lee connected David Benioff’s novel to the events of 9/11. The novel had been published in January of 2001, and so was not directed at those cataclysmic events at all, but Lee used the story of a man waiting out his last hours as a free man to meditate on that particular moment in American time. I didn’t feel the close connection to New York City, per se, so much as the connection to whatever was going on in our heads just after 9/11.

Tyler: Benioff impressively adapted the novel himself. That feat and his excellent novel City Of Thieves garner much respect from me.

Norman: I kept thinking about how in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 we had a kum-ba-yah moment, but then it quickly turned into fear of foreign people, especially anyone middle eastern. 25th Hour is at its core a movie about trust. Who can you trust? How do you know that you can trust them? What do they have to gain by betraying you? That kind of paranoia has only grown since, and so 25th Hour felt almost quaint seen today.

Tyler: I thought it prescient, at least in its details of Barry Pepper’s “cowboy” character Frank, playing high-dollar financial games with other people’s money. Frank might’ve jumped out a window in 2008 before Monty got out of prison.

Norman: And Philip Seymour Hoffman, playing a human version of Eeyore, is prescient as a man attracted to his 17 year old student. These issues – sexual power dynamics, age gaps, etc – have all come to the forefront in recent years, and Lee does an amazing thing with Hoffman. He’s pitiful, but we can sympathize with him. He’s certainly the most sensible and responsible of the male characters!

Tyler: Well, he does kiss his student.

Norman: But even in that moment he knows it’s wrong.

Tyler: Lee uses the familiar Spike-dolly move to great effect after Jacob presses his lips against that student’s. I don’t think Jacob knows it’s wrong until after that forced kiss—he retreats in self-loathing when she doesn’t respond in kind.

And therein is one of the things I think exceptional about 25th Hour. Jacob is in some ways the most sensible and responsible, and his work is certainly more honorable than Frank’s. But he becomes a predator for a terrible moment, and we have to accept that in feeling out his character.

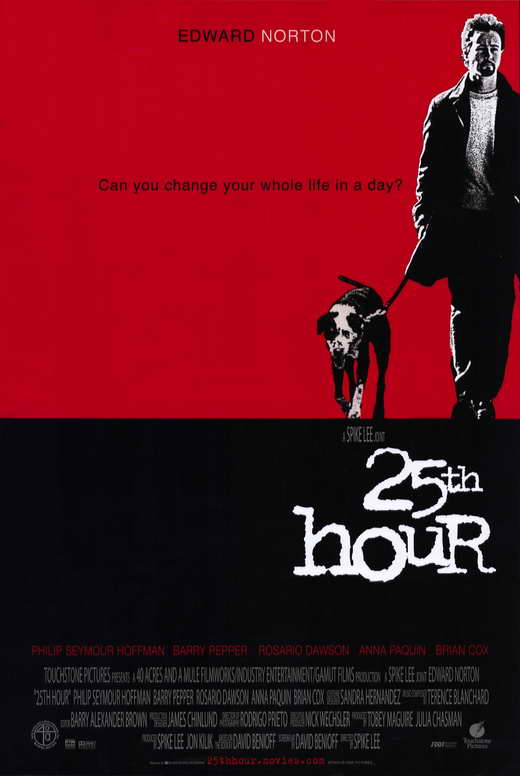

That brings us to Monty, the film’s main character, played by fantastic actor and legendary dickhead Edward Norton. Monty is a large-scale heroin dealer. He’s in with Ukrainian mobsters. He lives rather a lavish lifestyle on the quivering shoulders of the addicts to whom he peddles packets of dope. There is, in essence, nothing redeemable about him given what he does to make money. He’s a death dealer. Frank crushes the proletariat, but Monty kills them.

And yet we like Monty. We like his father, played by Brian Cox, who took drug money to save his bar. We really like Monty’s girlfriend Naturelle, essayed by Rosario Dawson, but she also lives a wonderful life thanks to people scoring smack. These characters from some angles are irredeemable for these transgressions.

25th Hour knows this, though, and therein—and this became especially clear to me in going back for this discussion—does it reach brilliance. Monty’s second scene is a wonder to look at, a walk of a dog on one of New York City’s rivers. It is also interrupted by one of Monty’s former clients, and the client is in terrible shape. Monty, much to his detriment, is annoyed, but the stakes of what he’s done are made immediately apparent.

Such contradictions are addressed—really, loudly declared—by Monty and Frank in scenes scattered throughout the film. It’s a self-awareness on Lee’s behalf that never overplays its hand.

We wind up falling for all of these characters, even maybe Frank, as we’re aware and regularly reminded of their horrific flaws. That’s impressive storytelling.

Norman: Yes, that is the strength of the movie. These are rich, multi-layered characters that we can both love and loathe at the same time. All of the actors, especially Norton and Dawson, nail this dynamic almost to a fault, because their characters are completely likable.

Where I found myself frustrated was in Lee’s use of monologues. Norton and Brian Cox each have pivotal monologues that, for me, just don’t seem to fit well with the rest of the movie. Norton’s seems to come nearly out of nowhere and Cox’s is too romantic for my tastes. But this is Spike Lee, a director given to bravado and bombast, a man never afraid to turn up the dramatic jazz score a little too loud.

Tyler: Oh, God, we’re at war. I adore both and believe them pivotal to the film’s success.

Norman: Shots fired!

Tyler: Norton’s monologue, in his own mirrored face, delivering this inverted love letter to the crazy beauty of what made New York and America beautiful melting pots—he throws in shade at his loved ones, then, but pivotally turns the derision on himself. It’s a tremendous performance, a wonderful montage, a terrific scene.

The Brian Cox monologue soundtracks one of the best sequences of cinema we’ve had yet this century. Bank it.

Norman: Norton’s monologue felt out of place to me. Likable though he is, this is not an expressive character. I didn’t feel like the character was speaking so much as Lee and Benioff were speaking.

Cox’s monologue was a fantasy, which hit me wrong after so much textured, clear-eyed character observation. I got the sense that they wanted to go out on a soaring note that hit on the expansiveness of the country and the possibilities of life, but really, this man is about to get gang-raped and the monologue fell flat to me.

If I were to isolate either monologue from the movie itself, I’d have to admit that they are impressive moments of cinema, but in context I could not deal.

Tyler: You do note a barely-underlying motivation the film very explicitly portrays: Monty, and men, fearing rape. I saw this theme noted in a headline years ago and didn’t read the piece because I was young and thought the characterization dismissive.

I was wrong. Monty’s abject terror at the vicious prospect of being sexually assaulted is so much a plot point that it fuels the film’s bloody emotional climax. Brass tacks, Monty is experiencing a particularly distilled shot of the fear that any woman any day anywhere might experience, say, walking through a parking garage.

This is not to dismiss the subject. There are notes here about how the American prison system is criminally overstuffed, and that assault in all those horrible forms is an immediate crisis that this country continues to facilitate. These are worthy points. None of this, truly, is to criticize this portion of the plot. But, there is a part of me that, watching Monty obsess and writhe, thinks “This must be how women feel, at perhaps a low simmer but always.”

Norman: Yeah, and if I were going to jail, I might worry about the same thing. I’m not the world’s toughest dude, though I don’t look half as good as Ed Norton. The fear is legitimate, but I do think the movie plays too much on that particular theme. I was drawn more to moments where Monty believes (probably rightly) that in seven years everyone will have moved on and he won’t have a chance to get a good job. His life is over, regardless of what unwanted sexual encounters he has or does not have.

Will Naturelle be there for him when he gets out? I’m not so sure. Will his dad even be alive? Not making that bet.

Tyler: I won’t contest much of that. At best Monty’d become a manager at Brogan’s, his father’s bar, an establishment that is unlikely to survive seven months, let along years, without Monty’s financial support.

I can’t believe you don’t dig the finale! I am emotionally beside myself.

It’s a portrait of the American dream.

Norman: I guess. It just did not work for me in this context. Monty probably deserves seven years. I hope things are great for him on the other side, but I don’t really want him hiding out in some town out west.

I’m glad I revisited 25th Hour. It was a movie I didn’t remember well and was pleasantly surprised by. I know I have some reservations, but this is definitely one of Lee’s better movies. It got me looking forward to his upcoming Highest 2 Lowest.

Tyler: I’m glad we gathered to discuss this one. I obviously have a deep affection for it. In the pantheon of Nine Eleven Films, it stands around the top.

Norman: I’m glad, too. Sometimes Lee’s stylistic idiosyncrasies annoy me, but I still love him as a person and as a director. This was well worth seeing again.