Spoilers for The Phoenician Scheme, as well as Rushmore and The Grand Budapest Hotel, contained below.

Tyler: Norman, it’s been a very long time since filmmaker Wes Anderson entered the scene. With The Phoenician Scheme, the 2025 release which we will be discussing here today, Anderson has proven an enduring artist for almost three decades. Does the work hold up these days? Is there a place in our tornadic world for the director’s very particular brand of whimsy?

Norman: There is no place in our world, because Wes Anderson’s world is really a parallel universe that only he has access to. He takes his cast and crew to film there, and then does post-production in this world. The question is: are we in the mood to look into his world for a couple of hours?

I’m rarely ready to go into WesWorld, but I usually get used to the vibe within 20 minutes.

Tyler: I think a lot of us moviegoers head in at least a little skeptical—having heard murmurs that Phoenician Scheme is “the most Wes Anderson Wes Anderson picture yet,” I wasn’t sure whether I would be driven away. The most recent work of his that I’d seen was a semi-short Netflix adaptation of Roald Dahl’s “The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar,” and, man, that was just too much for me. It was like a theatre, not theater, funhouse run riot. With that in my rear-view, as well as that “most Wes Anderson Wes Anderson movie” pithery, I was wary of The Phoenician Scheme.

That said, I was on the film’s side a little, too, as a couple of Rushmore worshippers in my life decided Scheme’s previews presaged an insufferable experience, and I wanted to have Anderson’s back, principally because he gave us The Grand Budapest Hotel, a masterpiece that likely transcends those early peaks, Rushmore and fan favorite The Royal Tenenbaums. So I was of two minds this time around. Cautious but sympathetic.

Norman: Anderson is to movies what the Ramones are to music. Bear with me. The Ramones came on the scene with something unique and fun and impossible for anyone to replicate except themselves. Anderson came on to the scene with something unique and fun and no one is going to even try to replicate it except these dopey AI-generated pictures. He has admitted that he has no interest in shifting on his style or approach. This means that he is officially a vibe. As I look back on his body of work, I’ve found that my favorite movies are the ones that feel loosest, most tender, not always strict about aesthetic approach. My top three are Rushmore, Royal Tenenbaums, and Moonrise Kingdom. As of late, he seems to be digging deeper into his aesthetic preferences in a way that both charms and distances me.

I went into Phoenician Scheme more than a little nervous.

Tyler: He’s getting political, though, too, in his own inimitable way. Both “Henry Sugar” and The Phoenician Scheme are about obscene wealth, and whether redemption can be found by those who amass it. For Wes Anderson, that’s startling. Grand Budapest achieved so much in depicting World War II—and, hey, if Quentin Tarantino can make that conflict his own, so can Anderson—but whether modern commentary could become part of the Wes approach never even occurred to me. It seemed so impossible!

Norman: It’s something I’m still getting used to. Anderson’s approach is so fanciful and quirky that it seems impossible to take seriously.

Tarantino is a good point of comparison here. He has made movies about WWII and slavery. His approach, like Anderson’s, is impossible to imitate, and, like Anderson, his eccentricities take center stage. Does his commentary on Nazism register as nothing more than a glorified exploitation/revenge movie? Kinda. But it’s also fun. But too fun to make me think deeply about WWII. I LOVE Inglorious Basterds, by the way.

Anderson isn’t dealing in real history here, but he is dealing in real ideas.

Tyler: See, I think there’s major depth in Grand Budapest. The moment where, after Gustav unleashes racist invective on the film’s hero Zero, Zero makes clear that he’s a refugee, Gustav’s immediate regret and apologies make it clear: the stakes here are higher than Max Fischer getting kicked out of Rushmore Academy.

Put it this way—Grand Budapest may be a far more accurate depiction of 1930s European horrors than Basterds is of early-‘40s Germany.

Norman: You are right. I’m thinking specifically of The Phoenician Scheme, though. These are big ideas about wealth and meaning, family, responsibility, etc, all filtered through Anderson’s imagination.

Tyler: Am I wrong, though, or does Scheme allow its characters a little more room to breathe, an occasional stillness that runs up against typical Anderson bric-a-brac?

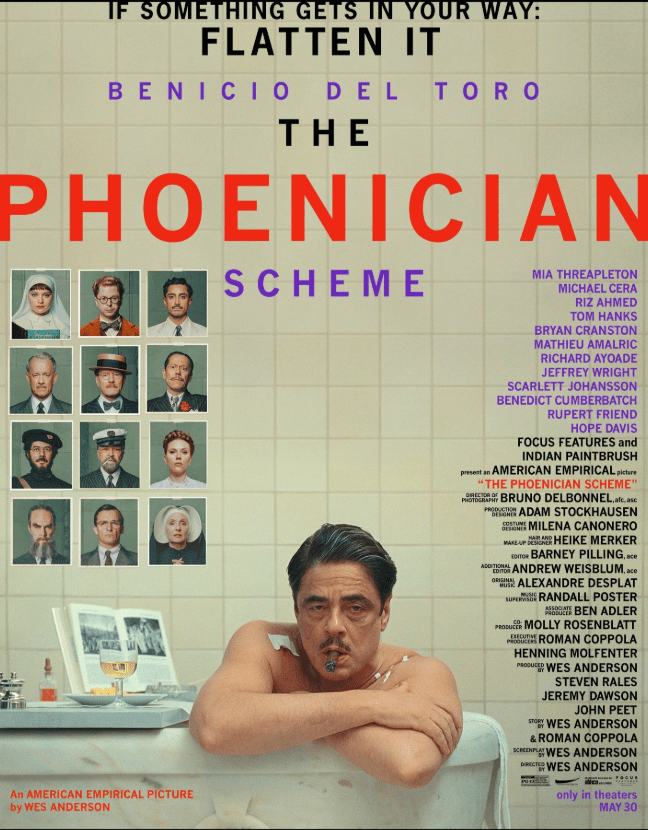

I think of the opening credit sequence, a single overhead shot of lead actor Benicio del Toro lolling in a soapy bathtub while attendants cater to his whims.

Norman: Yes. This one worked better than French Dispatch or Asteroid City. The lynchpin is Liesl (Mia Threapleton), a nun who has come out of the convent to deal with this estate. That character’s wrestling drove everything for me. She felt tangible and real to me in a way that few Anderson characters do.

Tyler: As an aside, how do you, a pastor, feel about the film’s depiction of faith and its applications in “real life?”

Norman: I have no idea what Anderson’s own religious views might be, but he gets this right. Faith is not worked out in a vacuum. It gets tested in real life situations, some of which are thrust upon you, as it has happened to Liesl. And when faith gets worked out in the real world, it is a process of wrestling, setting up ethical ideas that clash and cause problems. My favorite movie of all time, Black Narcissus, is about a group of nuns who have to encounter the real world.

Tyler: That’s good to hear. It reflects well upon Anderson’s treatment of his leads, which is often sympathetic and loving, even to louses like Royal Tenenbaum.

Norman: Yes. Another thing that really worked for me is that Anderson really focuses his attention on Korda and Liesl. There are famous actors in bit roles, as usual, but it never feels overstuffed. There’s room for real character development.

Tyler: Threapleton is terrific. Just as Anderson bravely cast relative amateur Jason Schwartzman opposite Bill Murray, and paired Ralph Fiennes with unknown Tony Revolori, he teams a young up-and-comer with a screen veteran. The two of them kill it together.

Norman: She was a revelation. She nails Anderson’s droll way, but also imbues Liesl with a sense of deep moral rigor.

How did you respond to the black and white scenes in heaven (?), I guess.

Tyler: Of all things, they reminded me of the visually-filtered sequences in The Zone Of Interest, a completely different and 100,000,000% more disturbing motion picture that, nonetheless, makes time for flitters of abstraction within a rigidly-stylized narrative. You and I broke down that movie, and I chalked those unusual scenes up to the intentions of a great artist at work. I wasn’t sure if they felt necessary, but I accepted their place in the film.

Norman: I hadn’t made that connection, but I see where you are going. As silly as they are in Phoenician Scheme, they somehow give heft to the morality of the film. They act oddly as a counterpoint. It was one way in which Anderson breaks a little from his usual that helped me along.

Tyler: This entire movie is about a camel trying to pass through the eye of the needle.

Norman: I really would be interested to learn about his religious convictions now!

Tyler: Some of the choices are rooted in basic morality. Liesl stamps her foot down upon learning that Korda uses slave labor.

In the end, and this is among the lovelier endings to any Wes Anderson movie I’ve seen, that camel appears to have passed through the needle.

Norman: YES! I wasn’t expecting to be moved, but I was genuinely touched by the ending.

Tyler: Anderson bringing around a seemingly-forgotten line about Korda being a good dishwasher? He and his daughter Liesl settling down with a deck of cards after a day of restaurateuring? My goodness, what a fine finale.

Norman: Though I have some misgivings about Anderson’s style, this was his best work since Grand Budapest Hotel.

Tyler: It’s a damn good movie.

The progression from Bottle Rocket, Anderson’s poised but comparatively raw debut, to this rock-solid picture, boy, it’s something to behold.

Norman: Here’s hoping he continues down this path!

Tyler: Agreed.